Why You Don’t Need to be Afraid of Performativity

In our study of 108 active higher education strategic plans, we discovered that by far, the most common theme in strategic plan goals or priorities was diversity, equity, inclusion and belonging (DEIB). Further, because DEIB-related initiatives were often distributed across all the goals in some plans, it became clear that some institutions were holistically reimagining what it means to create authentic welcome and belonging across all operational areas. This dynamic became an important component of our final reporting on this research. At the same time, we have also been listening to how audiences receive and respond to any DEIB-related institutional messaging across multiple channels. You’ve probably encountered some of the same things we have, especially one significant word:

Performativity.

If your work touches DEIB efforts, it can feel like this word lurks around, watching and waiting for a chance to jump out and brand you as a bad actor.

In our work, we’ve become so familiar with the hard decisions our clients make about their messaging and how hard it can be to know what the right thing to say is, even when they want to say the right thing so desperately. In our organizational and executive counsel practices, we’ve heard clients express concerns about backlash. You can imagine how close to the surface those concerns are during DEIB audits. Our creative and strategic institutional marketing and enrollment management practices can all require conversations about sensitive areas, as well.

Concern about audience response is fundamental. It is also fundamental to find some reassurance. We can tell you that if you try something and it doesn’t work and people respond with upset, you can choose to see that upset as an opportunity to deepen the conversation. Recognize that while a conversation is still happening, as painful as it may be, that while we are still communicating we are still in connection.

Speculation about the sincerity of DEIB efforts can be an immediate response to anything higher education institutions publish or say in this arena, for good reasons. Imagine a campus where a racist incident has occurred. Leadership issues a statement disclaiming this activity and promising action. Soon after, the message will be shared on social media by people who append those messages by posting something like, “We’ll see if this is just performative. I bet they are just saying this to make us be quiet.”

Let’s ask an important question: What work is the accusation of performativity doing?

In the colloquial sense, performativity refers to a gap between the content of value-laden statements we make and the actions we undertake afterward. When you write DEIB goals into your strategic plan, or you give a presidential address that mentions DEIB in some way, are you committing to something through these words? Asked another way, does anything happen just by virtue of saying something?

One philosophical theory of linguistic behavior would say that we do perform action through speech. This is called speech-act theory. One of its most famous proponents is British philosopher J.L. Austin (see the second edition of his book How to Do Things with Words [1962, Harvard University]). According to Austin, speech performs action. Speech is action and all speech is performative. We are responsible for our speech and its results.

Sometimes, the action is obvious. Think about your admission packet or portal. Admitted students see a message that says, “You’ve been admitted,” or, “Welcome to the Class of 2025!” Those are concretely performative acts because they create the conditions within which enrollment is possible. Admission has been performed.

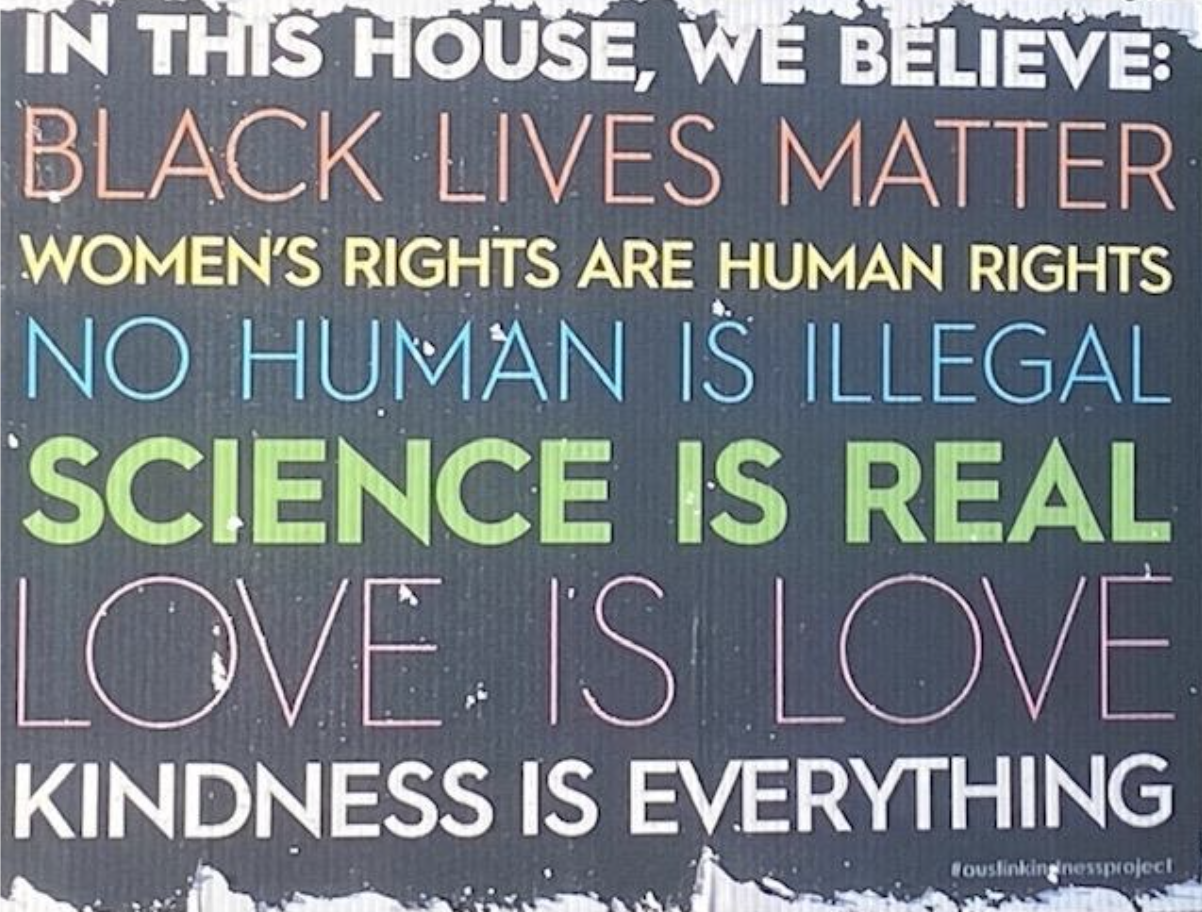

Now, let’s talk about yard signs. In my neighborhood, we have lots of signs like these.

This is a black sign with colored text that says, “In this house, we believe Black Lives Matter, Women’s Rights are Human Rights, No Human Is Illegal, Science is Real, Love is Love, Kindness is Everything.”

You may have seen photos on social media of a similar sign posted in a yard, but with the line “No Human is Illegal” blacked out with marker (the original tweet from Sept. 19, 2021, is here.).

This is a situation rife with possibility for speculating about performativity in its colloquial and philosophical senses (assuming this situation is real and not vandalism). The sign poster might think that posting an unedited sign is performative, because their own sign reflects the thoughtfulness with which they select their beliefs individually. On the other hand, a viewer might say that to post the sign after performing a deletion is meta-performative: a performative commentary on the performative nature of owning virtue-signaling yard signs.

Using our philosophical definition, we can ask what action the person who owns the sign has committed.

One consequence has been a fascinating disruption of audience expectation. It confounded people who saw the lines on the sign as a self-evident natural set, as a statement that makes sense as a totality. Perhaps the action performed by the sign is that it led people to reexamine whether their own beliefs are as coherent as they thought they were. Perhaps neighbors will behave differently toward the person who posted the sign because a new and unexpected commitment has been revealed. Is the sign poster responsible for that?

Speech-act theory’s argument that speech has consequences reminds us that what we say matters.

For higher ed audiences, institutional speech is an invitation to further dialogue rather than a final declaration. Being willing to bear the consequences of starting a conversation is itself an important responsibility. When audiences wield performativity as an accusation rather than an attribute of all speech, they are highlighting the space where consequences emerge. Audiences are responding to what they perceive, correctly, to be an invitation to hold us accountable to our commitments.

Accountability and responsibility are ethical precepts that underlie RHB’s advice when we counsel our clients to define their audiences and consider audience response before saying something. Here are some questions that underlie our advice, which you can use to guide your own statements:

- How have you arrived at the decision to speak into something and determine what the right statement and actions should be?

- What are you willing to be responsible for?

- What is your plan to point out the coherence between what you say and what you do?

- How will you prepare a response, ahead of time, if a conversation with your audiences doesn’t go the way you thought it would?

Spending some time thinking through these questions can reassure you that your statements are both supportable and supportive of action—and that you are prepared to maintain connection with audiences during the conversation you begin. We are always close by if you need a fresh audience, so be in touch.